CHAPTER 3.

INDIAN BURNING PATTERNS, 1491-1848

The traveler can but imagine the numbers of these dead tribes by the mounds of clam and oyster shells, many feet in thickness and many yards in extent, which mark the site of their former camping places. The gatherers of these sea-dainties have long since passed away, and even our first records tell of a time when wars, pestilence, and the gradual pressure on these sea coast dwellers by other tribes displaced from their hunting grounds in the east and south, had already done their work.

--Fagan 1885: 320

All the oak timber was owned by well-to-do families and was divided off by lines and boundaries as carefully as the whites have got it surveyed today. It can be easily seen by this that the Indians have carefully preserved the oak timber and have never at any time destroyed it

The Douglas fir timber they say has always encroached on the open prairies and crowded out the other timber; therefore they have continuously burned it and have done all they could to keep it from covering the open lands. Our legends tell when they arrived in the Klamath River country that there were thousands of acres of prairie lands, and with all the burning that they could do the country has been growing up to timber more and more.

--Che-na-wah Weitch-ah-wah (Thompson 1991: 33)

This chapter provides background on the primary Indian tribes and nations that lived on the Oregon Coast Range during the late 1700s and early 1800s. It then describes the principal burning practices these people used to create landscape-scale patterns across the Range and provides maps, figures, and tables of those patterns.

A. Historical Indian Nations: Background

Indians living in the Oregon Coast Range prior to European-American contact essentially viewed the land and sea as their supermarket, hardware store, and pharmacy (Lake 2002). The area naturally offers many biologically diverse and productive habitats which people exploited to provide personal and social necessities. Every ecosystem and vegetative assemblage was likely used and managed in variable intensities over time (Pullen 1996; Boyd 1999).

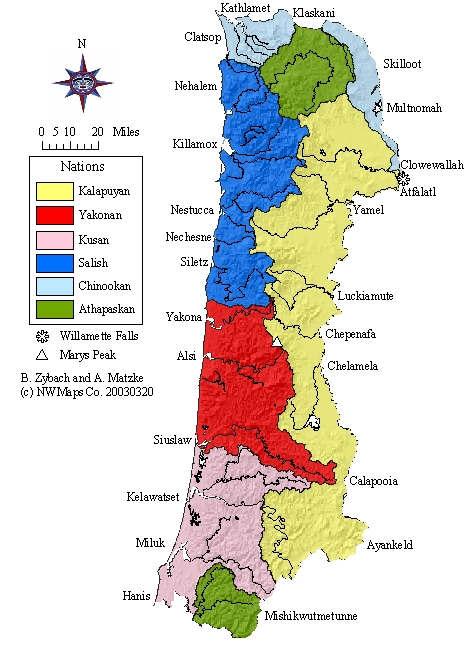

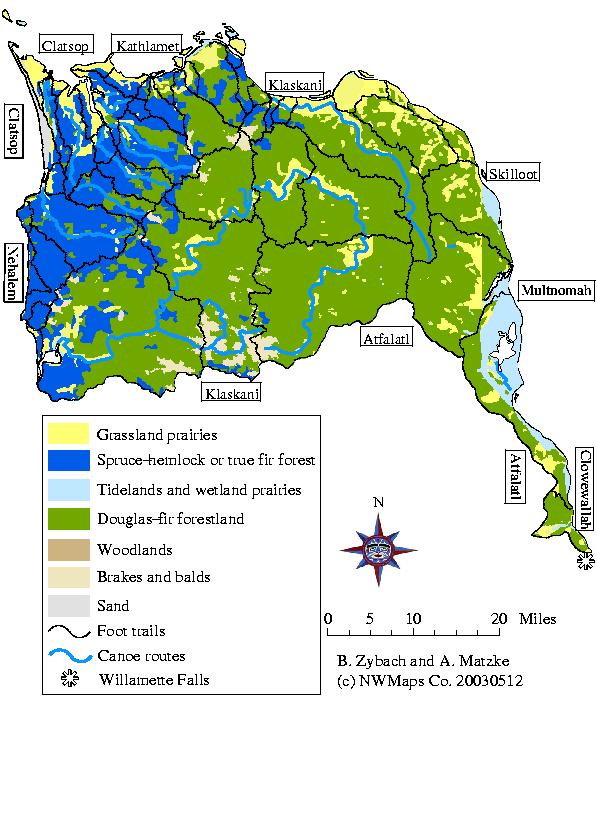

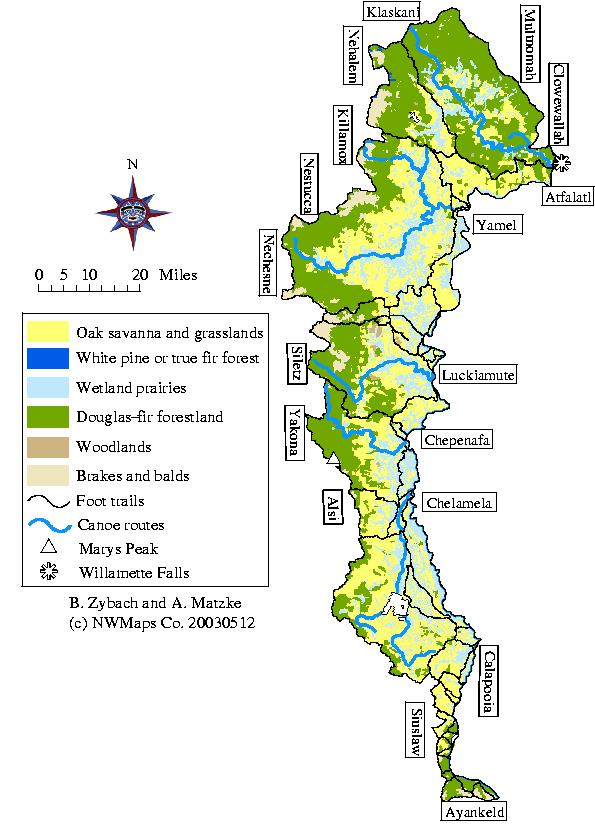

In early historical time there were at least eight Indian nations in the Oregon Coast Range and at least 26 distinct tribes. Map 3.01 shows the location of Coast Range Indian tribes during that period of time, from the late 1700s to the 1840s (Zybach et al., 1995). National boundaries were determined by the observations of early journalists, riverine and ridgeline travel corridors, and current understanding of precontact language and cultural affiliations.

For determinations of language I have relied on Ruby and Brown (1986) and Volume 7 of the Smithsonian's Handbook of North American Indians (Krauss 1990; Miller and Seaburg 1990; Seaburg and Miller 1990; Silverstein 1990; Zenk 1990a, 1990b, 1990c). The Smithsonian publications are probably somewhat more authoritative, but the Ruby and Brown book often provides additional insights and both use a common set of references. Both authorities are in general agreement as to the languages used by Oregon Coast Range Indians, with one notable exception: Ruby and Brown consider all coastal languages south of the Siletz to be of a single stock, Yakonan (1986: 4, 79, 97, 130, 206, 275); whereas Zenk (1990b: 568, 1990c: 572) lists Alsean, Siuslawan, and Coosan. In this instance, I decided to take a middle route--two languages: Yakonan (for the Yakona, Alsi, Siuslaw and Kelawatset tribes) and Kusan (for the Hanis and Miluk tribes). This intermediate position is consistent with current perceptions by modern tribal leaders (Whereat 2003: personal communication; Kentta 2003: personal communication).

Whenever possible, I tried to use the earliest commonly used spellings for individual tribes. Newer spellings and designations are generally less accurate phonetically (e.g., Atfalatl vs. Tualatin; Yamel vs. Yamhill; Killamox vs. Tillamook) and potentially confusing when using modern spellings of rivers (e.g., Marys River Indians vs. Chepanafa; Salmon River Indians vs. Nechesne; Upper Coquille Indians vs. Mishikwutetunne). Earlier spellings also help keep references clear as to time and possible pronunciation.

Map 3.01 Oregon Coast Range tribes and nations, ca. 1770.

Table 3.01 Oregon Coast Range tribes, rivers, and counties, 1770-1893.

|

Tribe |

Language |

River |

City |

County |

|

Northern |

|

|

|

|

|

Clowewallah |

Chinookan |

Willamette |

Oregon City |

Clackamas |

|

Multnomah |

Chinookan |

Willamette |

Portland |

Multnomah |

|

Skilloot |

Chinookan |

Columbia |

Ranier |

Columbia |

|

Kathlamet |

Chinookan |

Columbia |

Knappa |

Clatsop |

|

Clatsop |

Chinookan |

Youngs |

Astoria |

Clatsop |

|

Klaskani |

Athapaskan |

Clatskanie |

Clatskanie |

Columbia |

|

Nehalem |

Salish |

Nehalem |

Nehalem |

Tillamook |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eastern |

|

|

|

|

|

Atfalatl |

Kalapuyan |

Tualatin |

Tualatin |

Washington |

|

Yamel |

Kalapuyan |

Yamhill |

Yamhill |

Yamhill |

|

Luckiamute |

Kalapuyan |

Luckiamute |

Dallas |

Polk |

|

Chepenafa |

Kalapuyan |

Marys |

Corvallis |

Benton |

|

Chelamela |

Kalapuyan |

Long Tom |

Monroe |

Benton |

|

Calapooia |

Kalapuyan |

Willamette |

Eugene |

Lane |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Western |

|

|

|

|

|

Killamox |

Salish |

Tillamook |

Tillamook |

Tillamook |

|

Nestucca |

Salish |

Nestucca |

Pacific City |

Tillamook |

|

Nechesne |

Salish |

Salmon |

Rose Lodge |

Lincoln |

|

Siletz |

Salish |

Siletz |

Siletz |

Lincoln |

|

Yakona |

Yakonan |

Yaquina |

Newport |

Lincoln |

|

Alsi |

Yakonan |

Alsea |

Waldport |

Lincoln |

|

Siuslaw |

Yakonan |

Siuslaw |

Florence |

Lane |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Southern |

|

|

|

|

|

Ayankeld |

Kalapuyan |

Umpqua |

Yoncalla |

Douglas |

|

Kelawatset |

Kusan |

Umpqua |

Reedsport |

Douglas |

|

Hanis |

Kusan |

Coos |

Coos Bay |

Coos |

|

Miluk |

Kusan |

Coquille |

Bandon |

Coos |

|

Mishikwutmetunne |

Athapaskan |

Coquille |

Coquille |

Coos |

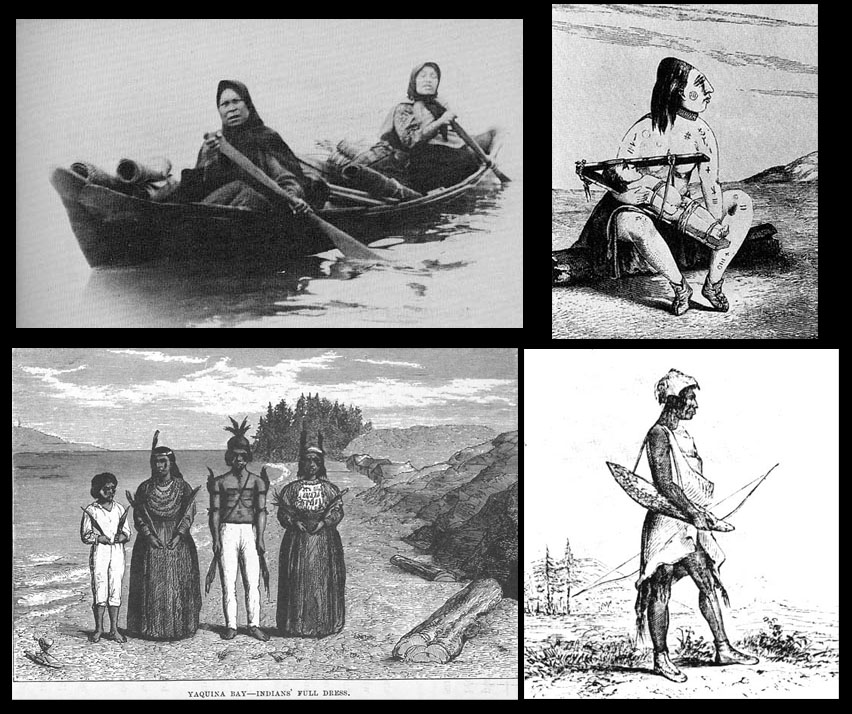

Table 3.01 lists the tribal groups shown on Map 3.01 and puts them into context with current river names, counties, and cities. Note the close correlation between modern river names and precontact tribes (also see Appendix B). Fig. 3.01 shows a selection of tribal members as depicted by a variety of photographers and artists in early historical time. The upper left photograph is of two Salish women, possibly Killamox, on a "trading trip" (Sauter and Johnson 1974: 29). The upper right drawing is of a Chinookan woman and her child. The drawing is thought to be made from a sketch by George Catlin and to depict a likely "superfluity of tattoos (Ruby and Brown 1988: 80). Note the flattened head of the woman, denoting "royalty" or upper caste, and the device used to create a similar effect on the child. This was a common practice among Chinookan people and certain adjacent tribes and gave rise to the general name of "flatheads" applied to several regional tribes and nations by early trappers and explorers (Carey 1971: 12). The lower left hand corner shows a family of Yakona Indians, near present-day Newport (Nash 1976: 150). This picture was drawn shortly after the Yaquina River basin had been withdrawn from the Coast Range Reservation and opened to white settlement. Note the postcontact dresses, pants, and shirt combined with traditional feather headdresses, tattoos and necklaces. It is thought that the modern clothing was inspired by early missionaries, who wanted local Indians to dress in a "more modest" fashion than provided by traditional clothing (Kentta 2003: personal communication). The lower right hand drawing was made of a Kalapuyan man, possibly of the Chelamela tribe, made in 1841 by Alfred Agate, a member of the Wilkes Expedition, near present-day Monroe, in Benton County (Wilkes 1845). Note the bare hills and isolated Douglas-fir trees in the background, the forbs at his feet, and the sealskin quiver; a sign of trade or other contact with adjacent tribes.

Fig. 3.01 Native people of the Oregon Coast Range.

Wilkes (1845) described the occasion of the latter drawing with this account:

Some wandering Callapuyas came to the camp, who proved to be acquaintances of Warfield’s wife: they were very poorly provided with necessaries. Mr. Agate took a characteristic drawing of one of the old men.

These Indians were known to many of the hunters, who manifested much pleasure at meeting with their old acquaintances, each vying with the other in affording them and their wives entertainment by sharing part of their provisions with them. This hospitality showed them in a pleasing light, and proved that both parties felt the utmost good-will towards each other. The Indians were for the most part clothed in deer-skins, with fox-skin caps, or cast-off clothing of the whites; their arms, except in the case of three or four, who had rifles, were bows and arrows, similar to those I have described as used at the north; their arrows were carried in a quiver made of seal-skin, which was suspended over the shoulders.

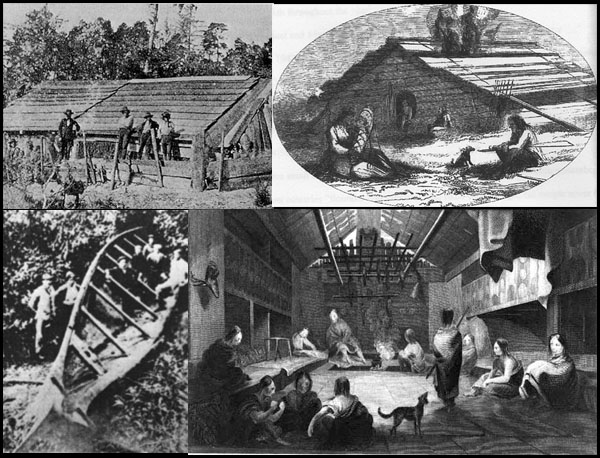

Large wood products. Precontact Indian people used large wood products throughout the Coast Range over long periods of time. Fig. 3.02 shows two principal uses of logs and planks by a variety of tribes. The two upper pictures show a photograph of a plank house near the mouth of the Umpqua River taken in the 1850s (CITE); the drawing is of a similarly styled home, possibly Kusan, from the same time period (CITE). The lower right picture shows another 1841 drawing by Agate (Oregon Historical Society negative # 4465) of the interior of a Chinookan lodge. Consider the amount of firewood needed to heat structures of this size. Also, the amount of lumber for construction and maintenance:

A single large house may have required as much as 70,000 board feet of lumber: One such structure near Portland, Oregon, was used continuously for 400 years and would have required between 500,000 and 1 million board feet of lumber during that period for maintenance and repair. And that is just one house, 55 feet wide and 120 feet long, home to forty-five to sixty people. (Suttles and Ames 1997: 273).

Fig. 3.02 Large wood products, Oregon Coast Range, 1788-1860.

The ocean going canoe in the lower left hand corner of Fig. 3.02 is typical of a type used by Salish people to travel and trade along the coastline (Sauter and Johnson 1974: 109). Such a canoe could easily hold more than twenty people, hundreds of pounds of seal, fish, or kelp, and facilitate the widespread trade of foods, baskets, slaves, or other items of common value. One of the earliest accounts of these canoes is by Haswell, off the mouth Tillamook Bay, in 1788 (Elliot 1928): "at this time we discovered a canoe with ten natives of the country paddling towards us on there nigh approach they made very expressive seigns of friendship."

On January 20, 1806, Clark described this type of canoe in detail (Sauter and Johnson 1974: 108-111):

The . . . largest species of canoe we did not meet until we reached tide-water, near the grand rapids below, in which place they are found among all the nations, especially the Killamucks and others residing on the seacoast. They are upward of 50 feet long, and will carry from 8,000 to 10,000 pounds' weight, or from 20 to 30 persons. Like all the canoes we have mentioned, they are cut out of a single trunk of a tree, which is generally white cedar, though the fir is sometimes used . . . In this way they ride with perfect safety the highest waves, and venture without the least concern in seas where other boats or seamen could not live an instant . . . In the management of these canoes the women are equally expert with the men.

Disease. A common tragedy among all of the Coast Range nations was the decimation of nearly all communities and families via diseases introduced by European, African, and American explorers and fur traders, beginning in the 1770s, and perhaps dating to much earlier times. Haswell, for example, made the following observations of people near the mouth of the Siletz and Salmon rivers in 1788 (Elliot 1926):

They were armed with bows and arrows they had allso spears but would part with none of them they had both Iron and stone knives which they allways kept in there hands uplifted in readiness to strike we admitted one of them onboard but he would not come without this weepen two or three of our visitors were much pitted with the small pox.

Haswell's observations were confirmed by Clark, who also extended the wide-ranging effects of the ca. 1770s smallpox epidemic, when he made the following observations near the mouth of the Willamette River in 1806:

I observed the wreck of 5 house remaining of a very large village, the houses of which had been built in the form of those we first saw at the long narrows of the E-lute Nation with whome those people are connected. I endeavored to obtain from those people of the situation of their nation, if scattered or what had become of the nativs who must have peopled this great town. an old man who appeared of some note among them and father to my guide brought forward a woman who was badly marked with the Small Pox and made signs that they all died with the disorder which marked her face, and which she was verry near dieing with when a girl. from the age of this woman this Disruptive disorder I judge must have been about 28 or 30 years past, and about the time the Clatsops inform us that this disorder raged in their towns and distroyed their nation

Introduced diseases inflicted a heavy toll on the social organization and infrastructure of Indian land management practices, particularly burning and trading networks. Catastrophic diseases between 1770 and 1850 removed at least 80% of the Indian population (Boyd 1999a). Settlement of whites followed closely behind Indian depopulation. Many areas of the landscape once commonly under Indian management and burning transitioned into “wilderness” (Anderson 1996). As a result, specific vegetation assemblages: orchards of oaks, berry grounds, basketry and root gardens, and rangelands managed for hunting missed Indian burning return intervals and forestation of prairies, berry patches, brakes, and meadows went unchecked (see Appendix F). What many white settlers came to witness was a transitional landscape moving from intentional management to one more influenced by natural processes. Remnant populations of Indians focused what limited management practices they could in face of disease, genocide and forced removal off their land base on to reservations.

A chilling eyewitness account of the impact of diseases on the populations of Nechesne and Siletz peoples first described by Haswell (Elliot 1926) is given by Talbot (Haskins 1948) as he traveled along Siletz Bay and the Salmon River (along the same route that currently connects the Chinook Winds and Spirit Mountain casinos) in early September, 1849:

Recrossing the horses, we extricated ourselves from this marsh and traveled down the shore of the [Siletz] bay. It was about three and a half miles long - greatest width one mile. The opposite shore was almost concealed from view by the fog, but it seemed to be heavily timbered. . . It is the custom of the Indians in this country to deposit their dead in canoes, and there are a great number of them along the borders of the bay.

Early this morning an old Indian entered our camp. He had come in a canoe from some distance up the bay, his attention having been attracted by a large fire which we had built last evening on the southern point of the inlet. He said that himself and another man, with their families, were the only residents on this bay - the last lingering remnants of a large population which once dwelt upon these waters. . .

. . . bidding our final adieau to the ocean, we struck northeast, following a small trail (present-day Highway 18] which led us over rolling hills covered with grass and a high growth of fern. About a mile to our right lay a handsome little fresh-water lake [Devils Lake], and beyond rose a succession of ridges and tall forests. Having come three miles through the hills we descended into a fine bottom lying along the banks of a stream about fifty feet wide [Salmon River] . . . There are no Indians living here.

1) North: Chinookan, Athapaskan, and Salish

The northern Coast Range was inhabited by Chinookan people from Willamette Falls to the mouth of the Columbia River, represented by the Clatsop (Silverstein 1990: 533-546; Ruby and Brown 1986: 30-31), Kathlamet (Silverstein 1990: 533-546; Ruby and Brown 1986: 11-12), Skilloot (Silverstein 1990: 533-546; Ruby and Brown 1986: 208), Multnomah (Silverstein 1990: 533-546; Ruby and Brown 1986: 142), and

Clowwewalla (Silverstein 1990: 533-546; Ruby and Brown 1986: 31-32) tribes. The Salish Nehalem tribe (Seaburg and Miller 1990: 560-567; Ruby and Brown 1986: 240-243) lived along the seacoast, to the south of Tillamook Head, an historical boundary between them and the Clatsop. Klaskani (Kraus: 530-532; Ruby and Brown: 29) people largely occupied the forested Tualatin Hills that bordered the Columbia River and the headwaters of the Nehalem River, to the north of Willamette Valley Kalapuyans.

Some of the earliest and most detailed accounts of the Chinookans and their local landscape were by Lewis and Clark, during their travels of late 1805 and early 1806. Clark, for example, described a Skilloot town in this manner:

a Short distance below the last Island we landed at a village of 25 houses: 24 of those houses we[re] thached with Straw, and covered with bark, the other House is built of boards in the form of those above, except that it is above ground and about 50 feet in length (and covered with broad split boards) This village contains about 200 Men of the Skilloot nation I counted 52 canoes on the bank in front of this village maney of them verry large and raised in bow.

On November 11, 1805, he made these observations:

dureing the last tide the logs on which we lay was all on float, sent out Jo Fields to hunt, he Soon returned and informed us that the hills was So high & Steep, & thick with undergroth and fallen Timber that he could not get out any distance . . . those people left us and crossed the river (which is about 5 miles wide at this point) through the highest waves I ever Saw a Small vestles ride. Those Indians are certainly the best Canoe navigators I ever Saw.

The eastern slopes of the Coast Range were inhabited by Kalapuyan people, who maintained tens of thousands of contiguous oak savannah acres through the practice of annual broadcast burns (Boyd 1986; Gilsen 1989). As with other tribes of the Coast Range, most Kalapuyans lived in tribes closely associated with a particular river (see Table 3.01; Map 1.03). The Atfalati (Zenk 1990a: 547-553; Ruby and Brown 1986: 5-6) occupied the mouth and headwaters of the Tualatin River; the Yamel (Zenk 1990a: 547-553; Ruby and Brown 1986: 274-275) lived to their south; along the Yamhill River; the Luckiamute (Zenk 1990a: 547-553; Ruby and Brown 1986: 109-110) lived to the south of the Yamel, along the Luckiamute River, the Chepenafa (Zenk 1990a: 547-553; Ruby and Brown 1986: 18-19) lived along the Marys River, to the south of the Luckiamute, although they likely shared common grounds, such as Soap Creek Valley, tributary to the Luckiamute. The Chelamela (Zenk 1990a: 547-553; Ruby and Brown 1986: 17) resided along the Long Tom River to the south of the Chepanefa. The Calapooia (Zenk 1990a: 547-553; Ruby and Brown 1986: 10-11) were more wide-ranging than other Kalapuyans during early historical time and apparently occupied much of the woodlands along the headwaters of the Willamette, Long Tom, and Siuslaw rivers, and traveled southward into the Umpqua basin.

The western Coast Range was dominated by Salish and Yankonan speaking tribes (see Map 3.01 and Table 3.01). The Killamox (Seaburg and Miller 1990: 560-567; Ruby and Brown 1986: 240-243) lived in the vicinity of Tillamook Bay, to the south of the Nehalem and to the north of the Nestucca (Seaburg and Miller 1990: 560-567; Ruby and Brown 1986: 240-243), who lived between the Killamox and Cascade Head, in north Lincoln County, which separated them from the Nechesne (Seaburg and Miller 1990: 560-567; Ruby and Brown 1986: 240-243), also known as the Salmon River Indians. To the south of the Nechesne were the Siletz (Seaburg and Miller 1990: 560-567; Ruby and Brown 1986: 202), who lived along Siletz Bay and extended southward as far as Yaquina Head, to the north of Yaquina Bay. All four tribes spoke Salish, the southernmost group of people to use this language.

To the south of Yaquina Head, and extending southward to Tenmile Lake between the Umpqua and Coos rivers, were the Yakonan speakers. The Yakona (Zenk 1990b: 568-571; Ruby and Brown 1986: 275-276) lived along the Yaquina River, the Alsi (Zenk 1990b: 568-571; Ruby and Brown 1986: 4-5) along the Alsea River, and the Siuslaw (Zenk 1990c: 572-579; Ruby and Brown 1986: 206-207). Haswell (1928) was the first to note differences in the Yakona and Salish people, when he observed in 1788:

The long boat in the evening returned alongside they had seen nothing remarkable except vast numbers of the [probably Alsi] natives they appeared to be a very hostile and warlike people they ran along shore waving white skins these are the skins of moose deer three or four thicknesses compleatly tanned and not penetrable by arrows these are there war armour they would some times make fast there bows and quivers of arrows to there spears of considerable length and shake them at us with an air of defyence every jesture they accompaneyed with hideous shouting

The following day Haswell sailed further north with his ship, where they encountered an entirely different response:

Made sail along shore at 11 A M there came alongside two Indians [likely Nechesne or Siletz] in a small canoe very differently formed from those we had seen to the southward it was very sharp at the head and stern and Extrememly well built to paddle fast they came very cautiously toward us nor would they come within pistol shot untill one of them a very fine look’g fellow had delivered a long oration accompaneying it with actions and jestures that would have graced a European oritor the subject of his discorse was designed to inform us they had plenty of Fish & fresh water on shore at there habitations which they seemed to wish us to go and partake of . . .

One line of speculation is that the Alsi people had already been subjected to European diseases and had determined the source of their problem as having arrived by sea, in the same manner and from the same direction as Haswell and his shipmates.

4) South: Kusan, Athapaskan, and Kalapuyan

The southern Coast Range was a mix of cultures, weather, and landscape patterns that reflected similarities to each of the other three subregions. The Kelawatset (Zenk 1990c: 572-579; Ruby and Brown 1986: 97-99) lived along the lower Umpqua River mainstem, and were the southernmost speakers of the Yakonan language. Their territory extended south to Tenmile Lake, which the Hanis (Zenk 1990c: 572-579; Ruby and Brown 1986: 79-81) are said to have claimed for the Wappato that grew there. They also lived along the Millicoma River, although it was named for the Miluk tribe (Zenk 1990c: 572-579; Ruby and Brown 1986: 130-133), whose territory included land south of Coos Bay to the mouth of the Coquille River, and then inland, to the present-day site of Myrtle Point. Both Hanis and Miluk spoke Kusan, although the Miluk are thought to have been largely bilingual; bordered on the north by the Hanis, and to the east and south by the Mishikwutetunne (Miller and Seaburg 1990: 580-588; Ruby and Brown 1986: 64-66) and other Athapaskan speaking tribes.

To the east of the Yakonan and Kusan people were the southernmost tribe of Kalapuyans, the Ayankeld (Zenk 1990a: 547-553; Ruby and Brown 1986: 276-277), who lived near present-day Yoncalla, south to present-day Roseburg or Winston. These people maintained the central Umpqua Valley in nearly the same manner that other Kalapuyan tribes maintained the Willamette Valley: that is, they used fire annually to broadcast burn great expanses of oak savannah and grasslands. A key difference with the Willamette Valley people is that the climate was drier, so grass and ferns grew less profusely and acorns were harvested from mostly black oak and tanoak, rather than white oak.

Fire was one of the most energetically efficient tools available to manipulate local ecosystems to produce or induce ecological qualities and derive socially desired products from the land (Kimmerer and Lake 2002). Through time, observations of natural processes, and experience, people learned to use fire to maintain areas of biological diversity and enhance the productive capabilities of the land (Anderson 1999; Turner 1991). As a result, they were able to consistently obtain a wide variety of foods, construction materials, medicines, and other products from known locations during certain seasons throughout the year. Such practices also reduced the likelihood of wildfire, and ensured personal and community safety when such events did occur (G. Williams 2000).

Indian burning patterns, by definition, are caused by people, and are the result of purposeful actions. Occasional fire escapements were probably a significant part of the landscape pattern created by daily firewood storage and use, situational patch burning, and seasonal broadcast burning. Trails would have been regularly cleared by fire and routinely harvested for firewood along their routes. The same would likely have been true of canoe routes, at least seasonally, along stretches of most low gradient streams and rivers throughout the Range.

The use of fire in the landscape varied from culture to culture over time, and according to circumstance. Differing climates, topographies, and plant assemblages led to--and resulted from--such differences throughout the region (Boyd 1999). All tribal groups used firewood, wove baskets, or manipulated vegetation that affected fuel structure and composition. Indian people managed oak savannas for acorns, and prairies primarily for seed, camas or other bulbs, or roots crops (Norton 1979). Indians on the coast used fire along coastal headlands affecting the production of berries, ferns, and facilitated more open wildlife habitat (Pullen 1996). Local knowledge of fire and fire's effects on different ecosystems increased predictability and certainty of such seasonally available resources (Turner 1991). Increased diversity, predictability, and certainty resulted in improved individual quality of life and social security for local communities (Anderson 1996).

Table 3.02 (Zybach and Lake 2003) describes three major types of Indian burning practices that affected landscape patterns of vegetation and provided definition to local wildlife habitat conditions: firewood gathering and burning, patch burning, and broadcast burning.

Table 3.02 Oregon Coast Range Indian burning practices, pre-1849 .

|

Type of burning |

Products and purposes |

Timing |

|

Firewood gathering and burning |

1-2 purposes: heat, light, cooking, boiling, cleaning, fuel stores, celebration, ceremony, security. |

Daily: concentrated near homes, trails, settlements and campgrounds. |

|

Patch burning |

1-2 purposes: hunting, berry patch maintenance, root fields harvesting, pest control, weaving materials, trail maintenance. |

Seasonal and situational. |

|

Broadcast burning |

Multiple purposes: stable wildlife habitat; curing seeds; hunting; viewing; transportation; weaving materials; acorn harvest. |

Seasonal: late summer, early fall for grasslands; late winter, early spring for brackenfern. |

Firewood gathering and burning involves the movement of fuels to specific locations, resulting in areas containing relatively little (or stockpiled) large, woody debris and spots of repeated, intense, and prolonged heat. Patch burning is defined as having a specific purpose and involving fuels within a bounded area, such as burning an older huckleberry patch, maintaining a trail, or clearing a field of weeds. Broadcast burning is the practice of setting fire to the landscape for multiple purposes and with general boundaries, such as burning a prairie to cure tarweed seeds, eliminate Douglas-fir seedlings, expose reptiles and burrowing mammals, and harvest insects (Zybach and Lake 2003).

Firewood gathering and use was probably a daily process for most families, hunters, gatherers, and travelers for hundreds and thousands of years throughout the Coast Range. Principal locations were probably located along the shores of estuaries and at the mouths of major tributaries. Low gradient riverbank floodplains were also likely locations of homesites and campgrounds. Springs, peaks, waterfalls, meadows, berry patches, root fields, filbert orchards, oat fields, camas patches, pea fields, and other favored locations were also the likely sites of seasonal camping and food processing activities that required intensive, localized firewood gathering activities.

The likelihood of most bonfires, campfires, oven fires, and sweathouse fires resulting in wildfire events was probably very low. Fires left unattended for the purpose or desire of spreading were probably fairly common, but such fires were intended to spread when possible and cannot be considered escapements. The cumulative results of widespread and systematic firewood gathering over time undoubtedly had a major impact on the location, distribution, and quantity of fuels consumed during wildfire, field clearing, or crop management processes.

Daily and seasonal trail clearing activities, combined with seasonal and occasional and seasonal brush clearing, hunting, seed curing, sprout-inducing burns, made year-around open field burning a likelihood. Areas most likely to be burned in this manner included ridgeline trail segments, hilltop balds, brackenfern prairies, berry patches, filbert orchards, and other travel corridor segments or croplands. The escapement potential of such fires was probably moderate, depending on weather, the fuels being burned, and the condition of burn boundaries.

Many areas (specific habitats or patches) across the landscape within different ecosystems were nationally, family or individual owned. Ownership of productive areas across the landscape was viewed as a care-taking socio-ecological responsibility. Indians managed many of the most productive hunting and gathering areas with fire. Parcels of land that could provide productive, abundant, and predictable natural resources provided foods, medicines and material goods for Indian people. A productive and diverse landscape reflected a wealthy and healthy social community. Fire was a ubiquitous tool used by Indian people to perpetuate ecological goods and services necessary for survival (Kimmerer and Lake 2002).

Seasonal broadcast burning activities varied from firewood and patch burning actions in two important ways: fire boundaries were not so clearly defined, and there were multiple objectives for burning. Large grass or fern prairies and extensive oak savannahs were maintained by seasonal broadcast burns for a wide variety of purposes, including land clearing, hunting, seed processing, weeding, insect harvesting, and enjoyment. Escapement likelihood of these actions was, like patch burning, probably moderate. The application of broadcast burning by Indians was viewed essential to maintain diversity and productivity of the landscape. The scale of such broadcast burning varied but could result in much larger expanses of land base if climate or weather intensified fire behavior (Lake 2002).

The development and maintenance of transportation corridors, extensive oak savannahs, prairies, berry patches, filbert groves, camas fields, lawns, and balds by Indian burning practices also resulted in beneficial habitat to a number of plant and animal species, providing sunlight, abundant food, ready transportation corridors, and certain types of cover. During wildfire events, these areas were not prone to being burned, or burned at relatively low temperatures, and could also function as "refuges" for threatened wildlife species.

Table 3.03 lists a range of native plant environments encountered by GLO surveyors in Alsea Valley (see Appendix D) between 1853 and 1897 (see Table 2.02). These descriptions were included in a national set of GLO survey instructions used from 1851 until 1910, and so each surveyor had an identical range of choices to select from. A column titled "Burning" has been added, to provide an approximate idea as to how often--and what time of year--the landscape needed to be burned in order to remain free of tree growth.

Table 3.03 Native plant environments of "Alseya Valley", 1853-1897.

|

Name |

Years |

Townships |

Burning |

|

Belt |

1893 |

14-7 |

Rare |

|

Bottom |

1853-1893 |

13-7; 14-7; 14-8 |

Situational |

|

Brake |

1856-1897 |

13-7; 13-8; 14-7; 15-7 |

Spring |

|

Burn |

1853-1897 |

13-7; 13-8; 14-7; 14-8; 15-8 |

Fall |

|

Cluster |

1891 |

15-8 |

Situational |

|

Forest |

1893 |

14-7 |

Rare |

|

Glade |

1893-1897 |

13-8; 14-7; 15-7 |

Situational |

|

Grove |

1893 |

14-7; |

Situational |

|

Meadow |

1891-1893 |

14-7; 14-8; 15-8 |

Situational |

|

Opening |

1856-1893 |

13-8; 14-7; 14-8 |

Situational |

|

Patches |

1893 |

14-7 |

Fall |

|

Prairie |

1856-1897 |

13-7; 13-8; 14-7; 14-8 |

Fall |

|

Scattering |

1878-1891 |

14-7; 14-8 |

Fall |

|

Swamp |

1856-1878 |

13-7; 14-7; 14-8 |

Rare |

|

Thicket |

1856-1893 |

14-7; 14-8 |

Situational |

|

Timber |

1856-??? |

13-7; 14-7; 14-8 |

Rare |

|

Trail |

1853-1897 |

13-7; 14-7; 14-8 |

Situational |

Table 3.04 is a list of food plants identified by the same surveyors, that they encountered in the various environments listed in Table 3.03. The timing of patch burns can be generally inferred by the length of time it took for fruits and berries to set, ripen, and be harvested, or the appropriate time to clear land for root digging or fiddleback picking. Local weather conditions (see Table 1.01) would have further dictated burning times.

Table 3.04 Seasonal locations of Oregon Coast Range Indian fires.

|

Food |

Species |

Years |

Townships |

|

Berries |

Blackberry |

1891-1897 |

13-7; 13-8; 14-7 |

|

Berries |

Gooseberry |

1891 |

15-8 |

|

Berries |

Huckleberry |

1891-1897 |

13-7; 14-7; 14-8; 15-7; 15-8 |

|

Berries |

Oregon Grape |

1856-1891 |

13-7; 14-7; 14-8; 15-7; 15-8 |

|

Berries |

Salal |

1856-1897 |

13-7; 13-8; 14-7; 14-8; 15-7; 15-8 |

|

Berries |

Salmonberry |

1865-1891 |

13-7; 13-8; 14-8; 15-8 |

|

Berries |

Thimbleberry |

1891-1893 |

13-7; 13-8; 14-7; 14-8; 15-8 |

|

Fruits |

Choke Cherry |

1856-1897 |

13-8; 14-7; 14-8; 15-8 |

|

Fruits |

Crab Apple |

1856 |

14-8 |

|

Grains |

Grasses |

1856-1893 |

13-8; 14-7; 14-8; 15-8 |

|

Nuts |

Filbert |

1853-1897 |

13-7; 14-7; 14-8; 15-7; 15-8 |

|

Nuts |

White Oak |

1856-1891 |

13-7; 13-8; 14-7; 14-8; 15-8 |

|

Peas |

Legumes |

1856-1893 |

13-7; 14-7; 14-8 |

|

Roots |

Brackenfern |

1853-1897 |

13-7; 13-8; 14-7; 14-8; 15-7 |

The plants listed in Table 3.04 provide a good beginning point toward realizing the great abundance and variety of food precontact Indians were able to cultivate through the regular use of fire. Table 3.05 provides a more comprehensive listing, and is generalized for the entire Coast Range, not just Alsea Valley (Zybach and Lake 2003). A more comprehensive listing is given in Appendix A. The column marked "Fire" denotes whether plants were dependent on regular disturbance for their survival, such as provided by fire, tillage, picking, and pruning, or whether they were merely tolerant of such actions.

Table 3.05 Principal native food plants of the Oregon Coast Range.

|

Food Type |

Food Name |

Fire |

|

Berries |

Blackberry |

XX |

|

|

Huckleberry |

XX |

|

|

Salmonberry |

XX |

|

|

Strawberry |

XX |

|

|

Thimbleberry |

XX |

|

Bulbs |

Camas |

XX |

|

|

Lily, Chocolate |

XX |

|

|

Lily, Tiger |

XX |

|

|

Onion |

XX |

|

|

Wapato |

X |

|

Fruits |

Crabapple |

X |

|

|

Chokecherry |

XX |

|

|

Manzanita |

XX |

|

|

Rosehips |

XX |

|

Grains |

Grass seed |

XX |

|

|

Indian peas |

XX |

|

|

Sunflower |

XX |

|

|

Tarweed |

XX |

|

Greens |

Dock |

XX |

|

|

Miner's Lettuce |

XX |

|

|

Nettles |

XX |

|

|

Seaweed |

X |

|

Mushrooms |

Chicken-in-the-woods |

|

|

|

Morrels |

XX |

|

|

Puffballs |

XX |

|

|

Shaggy Manes |

|

|

Nuts |

Acorns |

XX |

|

|

Filberts |

XX |

|

|

Myrtle nuts |

XX |

|

|

Pine nuts |

X |

|

Roots |

Brackenfern |

XX |

|

|

Mountain carrot |

XX |

|

|

Yampah |

XX |

|

Stalks |

Cat-tail |

X |

|

|

Fiddleheads |

XX |

|

|

Skunk cabbage |

X |

|

|

Thistle (Edible) |

XX |

Acorns, filberts, camas, wapato, tarweed, huckleberries, blackberries, brackenfern, nettles, tobacco and other "signature" food crops were often managed in select areas over long periods of time. Crops were maintained and harvested in discrete locations in which the dominant species—usually the crop species itself—was established within a few weeks or months time. This approach creates a condition that is called “even-aged” management. Access to croplands was provided by foot trails and/or canoes, depending on location.

A few native Coast Range food plants, such as seaweed or wapato, were mostly independent of burning strategies. Tidal actions and seasonal floods provided the disturbances needed for these plants. The harvest of food was not insignificant, and may have pointed to a much larger human population prior to the advent of disease. Clark, for example, noted in 1806, near the mouth of the Willamette:

. . . we recognized the man who took us over last night, . . . he invited us to a lodge in which he had Some part and gave us a roundish roots about the Size of a Small Irish potato which we roasted in the embers until they became Soft, This root they call Wap-pa-to the Bulb of which the Chinese cultivate in great quantities called Sa-git ti folia or common arrow head, . . . it has an agreeable taste and answers verry well in place of bread. . .

. . . at 8 miles passed a village on the South side at this place my Pilot informed me he resided and that the name of the tribe is Ne-cha-co-lee, I proceeded on without landing. at 3 P.M. I landed at a large double house of the Ne-er-che-ki-oo tribe of the Shah-ha-la Nation. on the bank at different places I observed small canoes which the women make use of to gather wappato & roots in the Slashes . . . I think 100 of these canoes were piled up and scattered in different directions . . .

A Portland State University researcher (CITE) has estimated that enough wapato grew on Sauvies Island alone to feed 15,000 people year around. Add that to the other wapato growing areas of the region, such as Columbia Slough and Wappato Lake in the Tualatin drainage, and the potential numbers of people that could survive on camas, acorns, brackenfern, salmon, clams, venison, etc., and the human "carrying capacity" of the Oregon Coast Range must have been tens of thousands of people during precontact time.

Energetically, many of the plants and wildlife species used and managed by people were also important to other plants and animals for habitat, cover, or forage (Norton et al. 1984; Todt and Hannon 1988). Table 3.06 lists important animal food groups for Coast Range peoples that were native to the area in precontact time. This table demonstrates the wide variety and abundance of important foods and trade items available to local people, as well as the response of favored species to regular fire management practices. This result was also dependent on the value of changed vegetation patterns to other desired species that used the same foods, or took advantage of bettered conditions of mobility, visibility, and cover.

Table 3.06 Principal native food animals of the Oregon Coast Range.

|

Food Type |

Food Name |

Fire |

|

Crustaceans |

Crabs, Dungeness |

O |

|

|

Crawdads |

X |

|

|

Shrimp |

O |

|

Fish |

Eels, Lamprey |

X |

|

|

Eulachon |

O |

|

|

Halibut |

X |

|

|

Salmon, Chinook |

X |

|

|

Salmon, Coho |

X |

|

|

Sturgeon |

X |

|

|

Trout, Cutthroat |

X |

|

Fowl |

Ducks |

XX |

|

|

Grouse, ruffed |

XX |

|

|

Geese |

XX |

|

|

Pigeon, band-tailed |

XX |

|

Insects |

Grass hoppers |

XX |

|

|

Stoneflies |

X |

|

|

Yellow jackets (larvae) |

XX |

|

Red Meat |

Bear, Black |

XX |

|

|

Deer, Blacktail |

XX |

|

|

Elk |

XX |

|

|

Gray Diggers |

XX |

|

|

Seals |

O |

|

|

Sea Lions |

O |

|

|

Squirrels, Gray |

XX |

|

|

Whale, Grey (occasional) |

O |

|

Shellfish |

Clams, Butter |

X |

|

|

Clams, Geoduck |

X |

|

|

Clams, Razor |

O |

|

|

Mussels, saltwater |

O |

|

|

Mussels, freshwater |

X |

|

|

Oysters |

X |

The relationship of Indian burning practices to wildlife habitat--especially habitat for such food animals as birds, ungulates, rabbits, and squirrels--was first discussed by Haswell aws he sailed along the southern Oregon Coast near Coos Bay in August, 1788 (Elliot (1926):

. . . this Countrey must be thickly inhabited by the many fiers we saw in the night and culloms of smoak we would see in the day time but I think they can derive but little of there subsistance from the sea but to compenciate for this the land was beautyfully diversified with forists and green veredent launs which must give shelter and forage to vast numbers of wild beasts most probable most of the natives on this part of the Coast live on hunting for they most of them live in land this is not the case to the Northward for the face of the Countrey is widly different.

D. Cultural Landscape Patterns

The combination of widely diverse landscape conditions and differing Indian cultures throughout the Coast Range led to significant differences in local and subregional landscape patterns. The following maps and eyewitness accounts describe and locate some of the principal differences that existed throughout each of the areas of the Coast Range.

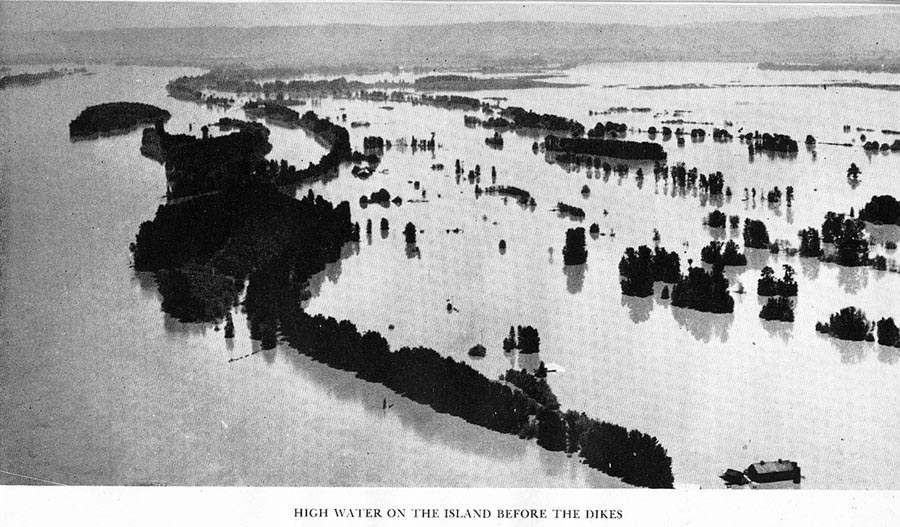

The northern Coast Range seems to have been heavily populated by people who trafficked almost exclusively along the Columbia River, with small prairies and floodplains serving to provide most needs for a land base. Trade with coastal seagoing peoples and upland Kalapuyans who managed plant foods for subsistence probably provided most of the necessary means needed to acquire most regional products. Fig. 3.03 shows pre-1941 seasonal flooding of Sauvies Island, at the mouth of the Willamette River. Between 1938 and 1941, 12,000 acres [of 24,064 total] of Sauvies Island were diked. Willow and cottonwood groves were cleared, and lakes drained. According to Spencer: "Most of the land within the dike had always been used in a state of nature with wild meadows producing pasture and hay. This had to give way because wild meadows depended on annual freshets for their luxurious growth" (Spencer 1950: 83), and: "Until recent years annual freshets from the Columbia and Willamette have covered most of its area for parts of each year. Its soil is deep and very fertile" (ibid.: 3).

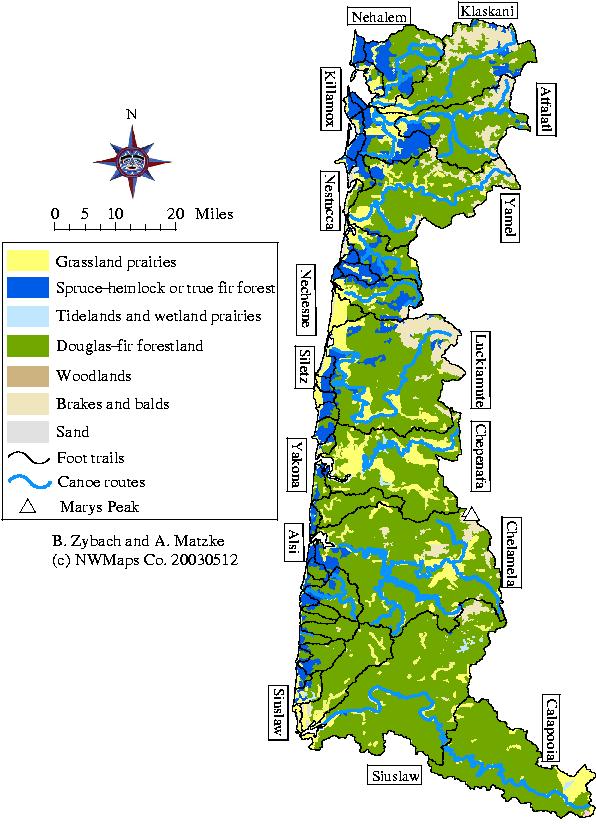

Fig. 3.03 Sauvies Island seasonal flood, pre-1941 dike completion.

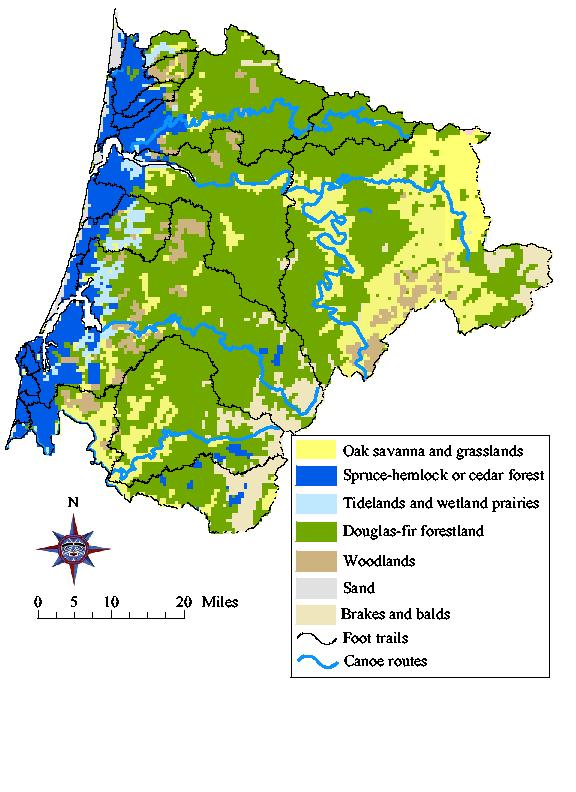

A map of the northern Coast Range, prepared from GLO survey notes (see Appendix D) and early vegetation maps (see Chapter 2) was constructed to display local landscape patterns as they likely appeared in early historical time (ca. 1800). Map 3.02 depicts the wetland prairies of the Multnomah, the tidal wetlands and adjacent prairies inhabited by the Clatsop and Kathlamet, and a well developed foot trail network between the two that was used and maintained by inland Klaskani. A significant string of prairies line the banks of the Nehalme River that was probably shared by both Nehalem and Klaskani, with Nehalem tending more toward the ocean and the Klaskani nearer the Columbia and Willamette rivers. The area is mostly dominated by an extensive stand of conifer forestlands, with hemlock, cedar, and spruce typifying the lands of the Salish people, and Douglas-fir populating most of the remainder.

Map 3.02 Northern Coast Range landscape patterns, ca. 1800.

The Willamette Valley was maintained by precontact Kalapuyan tribes as an oak savannah, through the annual use of extensive broadcast burning projects that likely took place every fall (Boyd 1986; Gilsen 1989). The result was a white oak savannah covering tens of thousands of contiguous acres, with hundreds of camas prairies, berry patches, root fields, and tarweed fields interspersed with "islands" of conifer trees and "gallery forest" riverine floodplains dominated by cottonwoods, bigleaf maple, ash, pine, true fire, and Douglas-fir.

Although Charles Wilkes did not travel south through the Willamette valley with other members of his expedition, he had access to their daily journals, from which he assembled his final report in 1845. He did travel extensively along the Columbia River, however, and made a brief trip into the northern part of the Willamette River:

. . . on the 14th [of August] we took leave of Vancouver. After proceeding down to the mouth of the Willamette . . .

. . . we were a good deal annoyed from the burning of the prairies by the Indians, which filled the atmosphere with a dense smoke, and gave the sun the appearance of being viewed through a smoked glass.

In early September, 1841, near present-day Corvallis, Wilkes (1845) recorded the following observations:

On the 10th, the country was somewhat more hilly than the day previous, but still fine grazing land. During the day they crossed many small creeks. The rocks had now changed from a basalt to a whitish clayey sandstone. The soil also varied with it to a grayish-brown, instead of the former chocolate-brown colour, which was though to be an indication of inferior quality. The country had an uninviting look, from the fact that it had lately been overrun by fire, which had destroyed all the vegetation except the oak trees, which appeared not to be injured.

As the expedition passed further south, Wilkes (1845: 221-222) reported:

The country in the southern part of the Willamette Valley, stretches out into wild prairie-ground, gradually rising in the distance into low undulating hills, which are destitute of trees, except scattered oaks; these look more like orchards of fruit trees, planted by the hand of man, than groves of natural growth, and serve to relieve the eye from the yellow and scorched hue of the plain. The meanderings of the streams may be readily followed by the growth of trees on their banks as far as the eye can see.

In contrast to the northern subregion, the eastern Coast Range contained very little conifer forestland. This was in part due to the annual burning practices of local Kalapuyan families, but also due to the relative fall drought experienced by the eastern part of the Range compared to the northern and western subregions (see Table 1.01 and Map 1.04). Talbot noted the difference in September, 1849 as he traveled along the current route of Highway 18, passing from the westward-flowing Salmon River, to the eastward-flowing Yamhill:

Near the Couteau, or summit line of the range there are many open spots, all covered with luxuriant crops of fern. Descending into the valley of the Willamette, we camped on a fork of the Jam Hill (Yamhill) river . . . We were much struck by the contrast in the appearance of the vegetation on this side of the mountain, parched and withered by the long droughth, while on the west slope we had left it fresh and green as in the early spring . . .

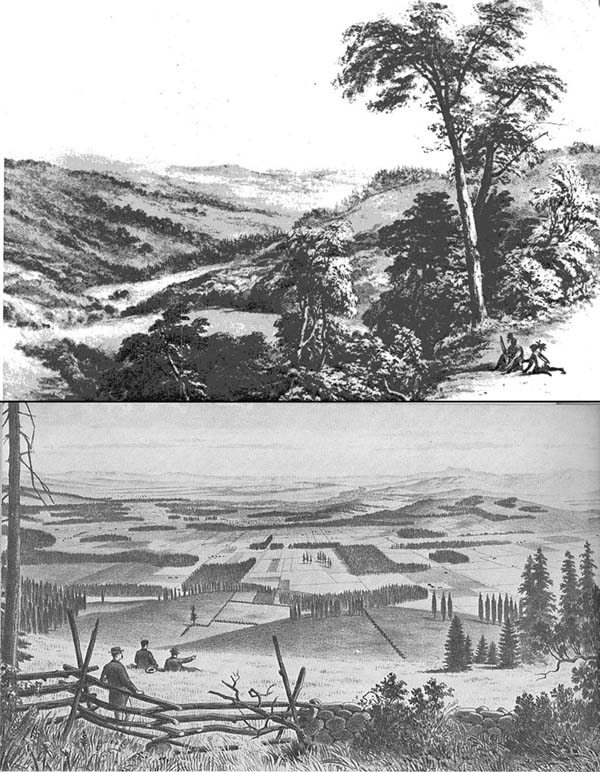

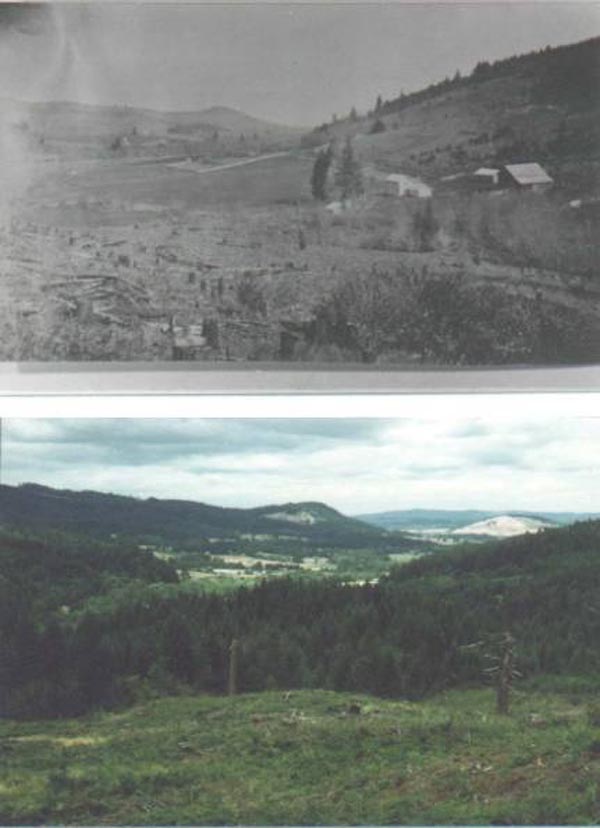

Despite this difference, once Indian burning was stopped in the late 1840s, much of the Willamette Valley brakes and grasslands began to develop Douglas-fir forests (see Appendix F). Fig. 3.04 shows the first steps in this process. In 1845, James Neall (1977) made the observation:

The leading features of the Willamette Valley and Tualatin plains were peculiar and strange to me as compared with any other country I had seen. Among the striking peculiarities was the entire absence of anything like brush or undergrowth in the forests of fir timber that had sprung up in the midst of the large plains, looking at a distance like green islands here and there dotting the vast expanse of vision. The plains covered with rich grasses & wild flowers looking like our vast cultivated fields, and where the rolling foothills approached the level valley these spurs would be sprinkled with low spreading oak trees, frequently with a seeming regularity that would seem unlike nature's doing, and at a distance like orchards of old apple trees.

Fig. 3.04 Willamette Valley, 1845-1888.

In 1885, forty years after the Willamette Valley had passed from Kalapuyan hands to American agriculturists and ranchers, the effect was strikingly similar. A somewhat florid writer of that time, writing of Benton County history, wrote (Fagan 1885: 328):

. . . a feast for the eye presented itself as the fertile prairie of the Willamette valley was espied from the far-off height of a crag or a mountain pass. And what was it like? For mile upon mile and acre after acre, tall wild grasses grew in wonderful profusion--one great, glorious green of wild waving verdure--high over the backs of horse and ox and shoulder high with the brawny immigrant. Wild flowers of every prismatic shade charmed the eye, while they vied with each other in the gorgeousness of their colors and blended into dazzling splendor. One breath of wind and the wide emerald expanse rippled itself into space, while with a heavier breeze came a swell whose rolling waves surged over the foot-hills, beat against the mountain sides, and, being hurled back, were lost in the far away horizon. Shadow pursued shadow in one long merry chase; the air was filled with the hum of insects, the chirrup of birds and an overpowering fragrance weighted the air. The river's bank was clothed in its garment of green foliage, while, the dark green forest trees lent relief to the eye. The impenetrable jungle of to-day, at this time was not, the smaller growth being kept low by Indian fires, while the timber land presented a succession of tempting glades open to movements on foot or on horseback .

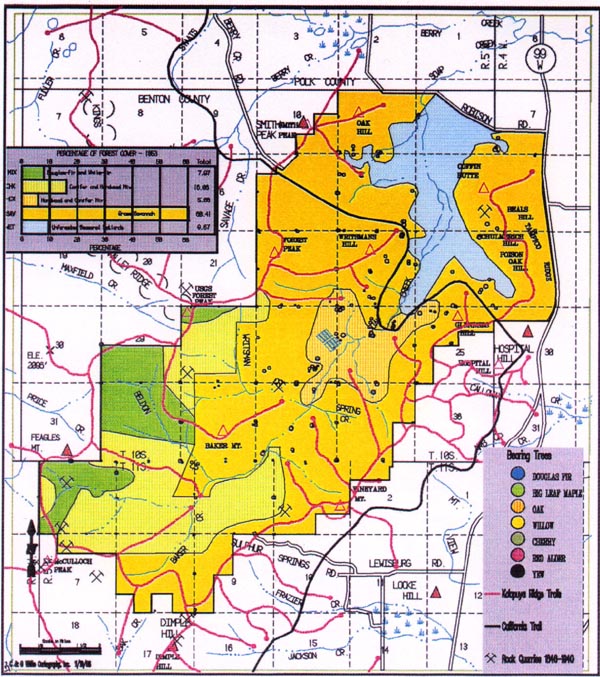

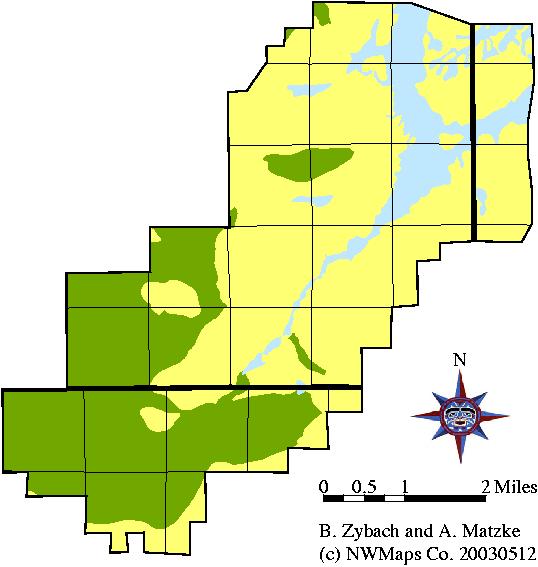

By 1885, then, significant brush had grown up and into the "peculiar islands" noted by Neall. Further, the survey lines of immigrant land owners turned into property lines and then fencelines, imposing straight lines into the landscape (see Fig. 2.03). To further track this process, the 15,000 acre Soap Creek Valley area can be used. Map 3.03 is a map of the Valley constructed by plotting every GLO subdivision and DLC bearing tree noted by the original land surveyors (Zybach 1999: 275-292). Inferences regarding tree diameters were used with a map of 1939 aerial photographs to derive a fairly accurate picture of local vegetation patterns in 1826. A more general use of the same notes was used to construct an 1850 pattern of the same area (Christy and Alverson 2003). The subsequent pattern, Map 3.04, is very similar and supports the use of GLO data for interpreting past environments [Note: an enlarged version of Map 3.03 is available online, and demonstrates the location, species, and diameter classes of the 250+ "bearing trees" that were plotted.]

Map 3.03 Soap Creek Valley, ca. 1826 GIS map.

Map 3.04 Soap Creek Valley, ca. 1850 GIS map.

Fig. 3.05 shows a 1914 photograph taken of Soap Creek Valley, showing that a combination of farming, grazing, and slashing has somewhat retained the "cultural legacy" of earlier generations of Kalapuyans; similar to the differences noted in Fig. 3.04 (Zybach 1999). However, a 1989 picture from the same perspective paints an entirely different picture. Farming practices that replaced burning practices have themselves been replaced with forestry practices. The oak savannah of the Kalapuyans and the open grazing lands and fenced pastures of early white settlers has been replaced by Oregon State University Research Forests' timber: the McDonald and Dunn forests (see Appendix F).

Fig. 3.05 Soap Creek Valley, 1914-1989.

Does the Soap Creek pattern hold true for the entire Willamette Valley? Map 3.05 was constructed in the same manner as Map 3.02, but the landscape is entirely different. Wetland prairies dominate the lowlands, and oak savannah dominates the uplands, with only ridgelines, occasional riparian areas, and steep valleys showing any significant amounts of conifer trees.

Map 3.05 Eastern Coast Range landscape patterns, ca. 1800.

3) West: lawns, corridors, and mosaics

The western Oregon Coast range landscape was dominated by the ocean, tides and bays rather than a major river and seasonal flooding. Saltwater, rather than freshwater, plants and animals formed an important part of daily and seasonal diets and recreation. Large canoes capable of sophisticated international trade excursions traveled up and down the coast for the entire length of the Coast Range, and along the Columbia River from the coast eastward, past the mouth of the Willamette River.

The northern part of the western Coast Range was opened to white settlement in the early 1850s, where white immigrants coexisted with small bands of Killimox that had survived the small pox and malaria epidemics that had devastated their own population and caused the extinction or near-extinction of many neighboring tribes. One such immigrant was Warren Vaughn, who apparently kept a journal and used it as the basis for his memoirs, handwritten in the 1880s (Vaughn 1923). Speaking of the early 1850s, when he first arrived at Tillamook Bay, he observed:

At that time, there was not a bush or tree to be seen on all those hills, for the Indians kept it burned over every spring, but when the whites came, they stopped the fires for it destroyed the grass, and then the young spruces sprang up and grew as we now see them.

The first person to accurately describe the mix of trails, brakes, balds, and bottomland prairies that characterizes much of the western Coast Range is Talbot (Haskins 1948), who traveled along the Siletz, Yaquina, Alsea, and Salmon rivers in late August and early September, 1849, on an exploration of the largely uninhabited area that would soon become part of the Coast Range Reservation, in 1856 (CITE). As he followed a Klickitat horse trail from Kings Valley, near the headwaters of the Luckiamute in the Willamette Valley, he made the following notes:

2 miles below our camp of last night we struck the main fork of the Celeetz [Siletz; he was actually following present-day Rock Creek] river flowing from the N.E. . . Crossing it we ascended the bank into a handsome prairie, extending several miles along the north side of the river, which from the junction of its forks takes a nearly west course [near present-day Logsden, at the fork of Rock Creek and the mainstem Siletz River]. The soil of the river bottom is very rich; grass growing most luxuriantly where not completely choked up by the fern - this plant usurping possession of nearly every open spot of ground. It grows here from eight to ten feet in height, and is quite serious empediment to travel. We encamped in an open prairie bottom about a mile long and a half mile in width, just where the river, changing its course, makes an abrupt bend to the north. We are surrounded on all sides by tall forests of pine, fir, spruce, hemlock, etc., which gave quite a sombre [sic] appearance to this sequestered valley . . . There are no Indians residing permanently on this river, and no trails going further down; the one which we have followed thus far crossing the river here and striking south [toward the Yaquina River, near present-day Toledo].

Talbot subsequently went as far south as Alsea Bay, before returning north along the coast. He reached Yaquina Bay on September 3:

Moving camp we came two miles along the shore of the bay; thence striking north, traveling three miles through an open rolling country covered with fine grass and some smal[l] patches of fern and thistles. The soil here appeared to be very rich, and was well-watered by numerous little springs.

From Yaquina Bay he continued northward, toward Siletz Bay:

Our road gradually improved as the mountains, receding, left a beach of open land extending from the top of the precipices bordering the ocean to the foot of the steep timbered acclivities, a space varying from one-fourth to half a mile in width, well watered, with rich soil, bearing a luxuriant crop of clover, grass, and their usual concomitant of fern. . . we came to the upper part of Celeetz [Siletz] bay, where we encamped on a small prairie covered with fine bunch-grass and clover.

. . . We soon constructed a small raft for ourselves and baggage, the shore being strewn with thousands of drift-logs. . . we were glad to substitute in its stead a fine large canoe which we found concealed among the bushes on the opposite bank. It was after night before all had crossed, and we camped a hundred yards from the shore, at the edge of a pretty grassy prairie which borders the bay.

In the 1850s, the time of initial white settlement in the area, the Alseyah Valley existed as a series of prairies, brakes, balds, openings, patches and meadows connected by a network of foot trails, horse trails, and canoe routes, and bounded by stands of even-aged forest trees, burns, seedlings and saplings. This condition has been described as "yards, corridors, and mosaics" (Lewis and Ferguson 1999). Lewis and Ferguson initially used the phrase to describe a cultural landscape pattern maintained by Native people who lived in the boreal forests of Canada and Alaska (ibid.: 164, 172-178), but determined that similar management patterns were also used by people in the conifer forests of the Rockies and Sierra Nevadas (ibid.: 164), northwest California (ibid.: 167-168), western Washington (ibid.: 168-169), Australia (ibid.: 169-170), and Tasmania (ibid.: 170-171). These researchers found that in each instance, fire was the tool most commonly used to establish and maintain grasslands and other openings ("fire yards"), bounded by stands of trees and open transportation routes ("fire corridors"). Fire was also the agent that entered unmanaged forested areas, whether by human cause or lightning, and caused burns that regenerated to a shifting mosaic of even-aged stands of seedlings, saplings, and trees (ibid.: 164-165).

The existence of significant western Coast Range meadows and prairies in early historical time was demonstrated in Chapter 2 and in Appendix D with the "Alseya Valley" example. The transformation of grasslands to forestlands during historical time was shown with the Soap Creek Valley example in the previous section. Fig. 3.06 (photos by Zybach and Lapham 2003) shows persistent vegetation patterns that still exist in Alsea Valley to this time: the "cultural legacy" of past Alsi Indian land management practices. These pictures were taken in spring, 2003 (see Appendix H). The upper left picture is near the single "Indian Trail" crossing of the Alsea River that connected the Willamette Valley to Alsea Bay in 1856 (see Fig. 205), and shows an early oak prairie that was first surveyed in 1856. The lower left picture is a long riparian meadow (or glade) adjacent to Alsea River, directly behind an isolated Douglas-fir old-growth and just south of a popular campground and boat launch. There is no evidence that trees ever became established here (except along the riverbank to the left) at any time since the 1850s. The upper right photo and the lower right photo were taken about five miles distance from one another, in two locations believed to have been Alsi (or their predecessors') townsites in precontact time. In all four instances, the fire-dependent landscape patterns of the 1850s have been largely maintained by subsequent management actions of agriculture, grazing, and logging.

Fig. 3.06 Alseya Valley prairie relicts, 2003.

Map 3.06 was constructed in the same manner as Maps 3.02 and 3.05. The principal differences are a better developed ridgeline trail network than North (more foot traffic; better access to inland resources; better ridge alignments) and East (flat topography; seasonal wetlands; few impediments in any direction); more brakes, balds, and bottomland prairies than the North, far less savannah and oak woodlands than the East; far less canoe usage than the North, but far more than the East; and a transportation and trade focus on coastal estuaries that establishes a radiant trail network from those locations, which hardly exist in the North, and don't exist at all in the East. Finally, there is a much more extensive and pure Douglas-fir forest component than in the North (lots of spruce/hemlock forest) and the East (very little conifer forest of any kind).

Map 3.06 Western Coast Range landscape patterns, ca. 1800.

Vegetation of the southern Coast

Range reflects the cultural and topographical features of the landscape--that

is, it is a distinct mix: combining the wapato and floodlands of the north,

with the oak savanna and camas of the east, and the even-aged conifer forests,

inland prairies, and coastal grasslands of the west. Landscape management actions

were also mixed, when compared to the other three subregions: the use of wetland

prairies of the Coos and Coquille estuaries are reminiscent of the uses of

Columbia River tidelands, the central Douglas-fir forests and inland prairies

connected by foot trails are similar to the western Coast Range subregion,

and the black oak and tanoak savannah of the Umpqua were managed with annual

fall broadcast burns, similar to the way Kalapuyans managed the white oak savannah

lands of the Willamette. Wilkes (1845) describes the process of periodic, low-intensity

fires that were used to maintain such savannah conditions, although he seems

to have misinterpreted the purpose of these fires:

During the day they passed over some basaltic hills, and then descended to

another plain, where the soil was a fine loam. The prairies were on fire across

their path, and had without doubt been lighted by the Indians to distress our

party. The fires were by no means violent, the flames passing but slowly over

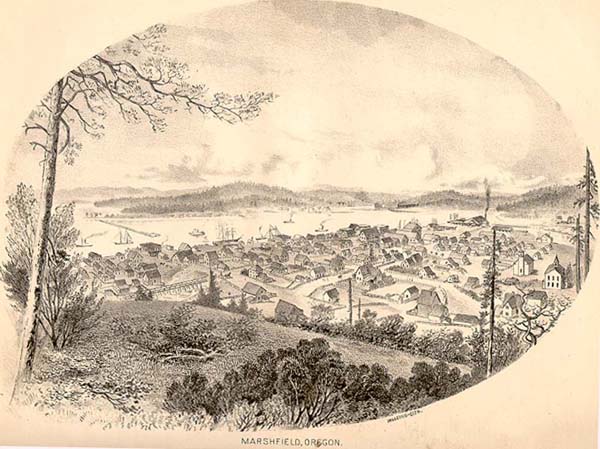

the ground, and being only a few inches high. Fig. 3.07 is a picture of the

town of Coos Bay in 1888, when it still went by the name of Marshfield. The "cultural

legacy" of low-lying prairie lands and sparsely timbered hillsides show

a disturbance history based on both floods and fire. The acquisition of prime

Indian lands by subsequent white settlers is also similar to the history of

the remainder of the Coast Range.

Fig. 3.07 Coos Bay, 1885.

Map 3.07 of ca. 1800 southern Coast Range vegetation patterns also presents the "mixed" picture of landscape patterns that characterizes the southern Coast Range today. The eastern oak savannah/woodlands pattern is similar to that of the eastern Coast Range, but likely had better developed canoe routes and foot trails. The central portion of the area is largely an even-aged stand of Douglas-fir, with limited trail access, similar to Athapaskan lands to the north. And, as with the north, the Athapaskans maintained a trade connection to the coast via a riverine townsite. One major difference from the other areas, though, is the extensive series of coastal sand dunes that exists between Coos Bay and the mouth of the Siuslaw; however, the total amount of land taken by these dunes is relatively small when compared to the entire area.

Map 3.07 Southern Coast Range landscape patterns, ca. 1800.

Lightning has been most commonly assumed as the source of historical fire on the Oregon cost range landscape (Agee 1993:54-55). The role of lightning fire vs. Indian burning in shaping fire regimes that produced varying vegetation patterns of the Coast Range has only been generally described (Boyd 1986; Boyd 1999). The role of Indian burning is most commonly attributed to valleys and lowland areas, and little evidence has been put forward to as to when, why or how Natives used fire in mountainous areas (Agee 1993:56). The lack of understanding by many scholars of the specific uses and application of fire by Indians in particular vegetation communities altering the fire regime has contributed to the dismissal of Indian burning as an important factor in shaping the composition, structure, diversity, and productivity of coastal forests and prairies (Vale 2002). Climate is a significant driver in potential vegetation assemblages at long time scales (hundreds to thousands of years). Potential ignition of fires by lightning is guided at a broad level by climate and weather events. Indian burning practices which adapted to and considered the greater influence of climate and seasonal influence of weather, has been overlooked as a significant driver in shaping vegetation assemblages and the rate of forest secession (Whitlock and Knox 2002). Indian burning practices were selective and specific to habitats across the landscape, valleys to mountains, capable of arresting forest secession that affected vegetation assemblages at shorter time scales (decades to centuries) resulting in altered fire regimes (Martinez 1993:27). Indian burning practices across the landscape influencing the continuity, structure, and availability of fuels potentially reduced negative effects of catastrophic wildland fire (Williams 2000).

White (1999: 47) makes a point that has bearing to this research when he points out: "Indeed, tribal divisions did not differentiate the villages of the Puget Sound region as well as the cultural divisions of inland, river, and saltwater—divisions first mentioned by American settlers and later adopted by anthropologists." These divisions hold true also for the Oregon coast Range. Both eyewitness accounts and historical maps show significant differences in the use of fire by river (Chinookan), saltwater (Salish, Yakonan, and Kusan), and inland (Kalapuyan and Athapskan) peoples. Further, there is a marked difference between the "inland" burning practices and resulting landscapes of Athapaskans, who tended toward dense Douglas-fir forestlands, and Kalapuyans, who maintained open oak savannas.

In precontact and early historical time, native plants were systematically managed by local Indian communities in all river drainages of the Oregon Coast Range (see Map 1.03). Firewood burning was a daily occupation by many precontact Indians. Patch burning practices were more likely to take place during seasonal periods, but also could be performed at about anytime weather and fuel conditions permitted. All historical accounts of broadcast burning activities in the Coast Range occur during two fire seasons: late winter/early spring "fern burning" and late summer/early fall "field burning". In this manner, seasonally desiccated ridgeline brakes and bald peaks could be burned whenever a drying east wind came up for a few days anytime from late February to early May. Valley grasslands, coastal headlands, oak woodlands, and tarweed fields were more likely to be burned in August or September, after vegetation had been dried by summer drought. East winds (see Map 1.08) were a factor that increased the likelihood of late summer/early fall broadcast field burns entering forested areas and developing into wildfire events.

Native food plants typically existed in relatively pure, even-aged patches or fields, and often bordered fallow mosaics (or "stands") of conifer trees; also generally characterized as existing in even-aged groupings of a single, dominant species. Stands of shorepine, Sitka spruce, Douglas-fir, noble fir, and western hemlock differed from managed areas in that they were probably not established or maintained for a distinct purpose, such as food, fiber or tobacco production. Because of the even-aged nature of these stands, it is likely they were established by seeding following either a forest fire, or the abandonment of a fire-dependent crop (see Appendix F).